Global Climate Change

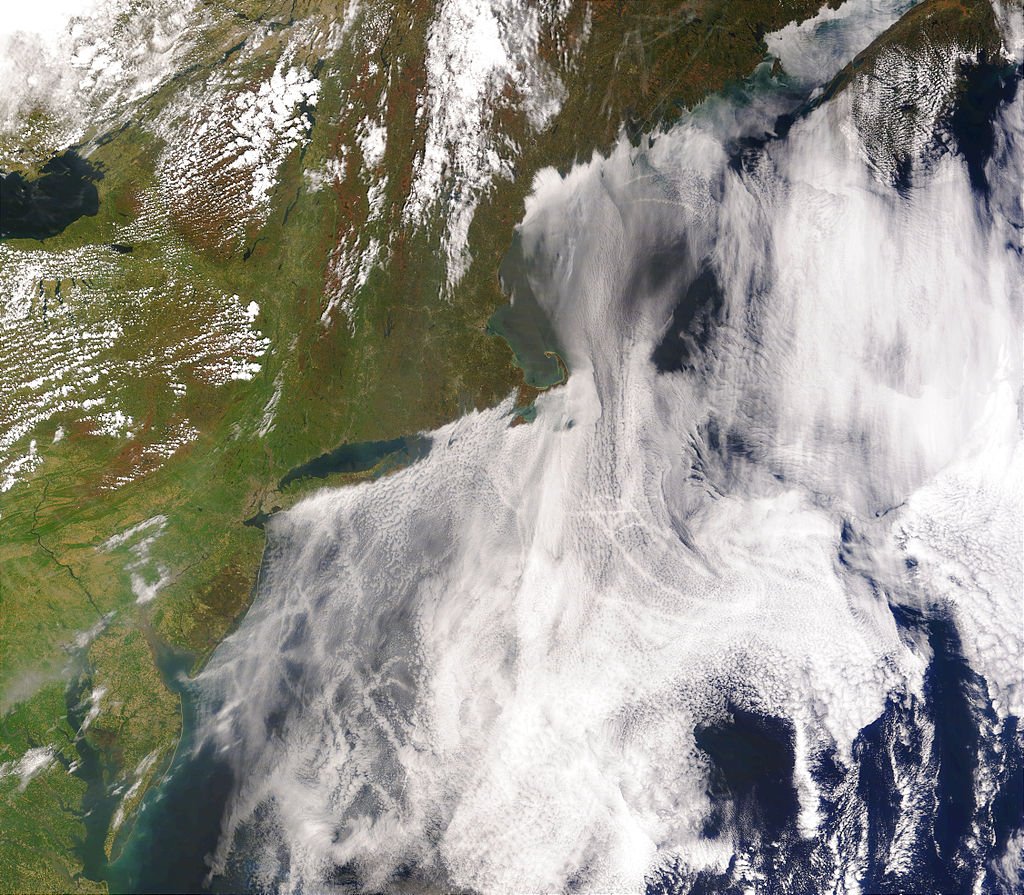

“The Earth’s climate is changing. Rising global temperatures will bring changes in weather patterns, rising sea levels and increased frequency and intensity of extreme weather. We need to avoid making the problem worse, so cutting carbon emissions is a priority. But all of us; individuals, businesses, government and public authorities, will also need to adapt our behaviour to respond to the challenges of climate change” (DEFRA, 2009). The essay brings out the key differences between the approaches to flood risk management in the UK and the Netherlands with the help of illustrations. References have been made to the authors deemed relevant.

There is a high degree of agreement between different authors and organisations regarding the impacts of climate change. To name a few, Scoones, 2004; Parry, IPCC, 2007; United Nations Environment Programme, 1993; Crawford, Dawsonera, Mehmood and Davoudi, 2009) discuss two most significant problems affecting coastal countries are, flooding resulting from the rise in sea levels and coastal erosion.

Climate Change in Britain

Britain has a maritime climate that makes it one of the wettest countries in Europe. UK is protected by cliffs from flooding. In the 1990s, flooding was not seen as a major problem in the UK and the floods in Midlands in 1998 were regarded as an anomaly. In 2000, it was estimated that the inland flooding in England could cost over 1 billion (W. Finlinson, D. Crichton, S. Evans, J. Salt and S. Waller and the Loss Prevention Council, 2000). Only three weeks after the publication, England experienced the wettest autumn since 1766 that flooded 10,000 properties from York to Lewes which cost insurers 1.3 billion. It was realised that climate change was responsible for the severe flood damage (P. Pall et al., 2011). 2013 – 2014 has been the wettest winter in 2 and a half centuries in Britain and some of the worst flooding in decades with more than 800 properties affected in 2014 floods (gov.uk, 2014). Since 1994, almost all the biggest floods in the UK happened in England and Wales1. England is densely populated. Hence, it is difficult to find plots that are not at risk of flooding. A population increase of 18% between 2008 and 2033 has been estimated (ONS, 2010). The highest number of new build in flood hazard areas can be found in the South East and the increase in the population density has been estimated to rise by 20% by 2033 (TCPA, December 2011).

Climate Change Planning Policies in the UK

On the policy front, at national scale, the main focus of UK climate change policy has been on carbon budgeting, reducing carbon emissions and carbon trading as set out in Climate Change Act, 2008. At regional and local authority scale, the main policy focus has been strategic and adaptive, dealing with the prediction and management of the impacts of the future climatic events such as sea level rise and river floods that have the potential to disrupt transport networks, infrastructure and services, and economic activity, and which affect emergency planning. Knight and Harrison discuss the resources available to inform local and strategic policy and planning for future climate change impacts include The Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change (2006); The Pitt Review (2008); UKCIP (2009); The Lawton Review of England’s Wildlife Sites and Ecological Network (2010). However, Knight and Harrison also identify that the disjunction between policies objectives is due to the lack of clear, strategic national guidance available to local authorities. These policy reviews and instruments successfully identify the major climate change issues at local and regional levels but fail to provide a national scale framework for actions on these issues. They are all advisory and not statutory. They generally inform on the scientific background but not on planning policy. The extent to which the national scale policy can and should be replicated regionally remains unclear (TCPA, December, 2011).

Historically, planning has always been in a frame of blame if anything ever went wrong including the natural disasters such as flooding. After 2007 floods, Sir Mike Pitt made 92 recommendations in the Pitt Review which the government and all the other key players agreed. The need for strong planning controls and flood risk assessments at both plan and site level and importance of sequential testing for both building and planning was realised (Pitt Review, 2008). Flood avoidance and mitigation remains a priority for planners. The storms that hit the UK in autumn 2013 and January 2014 has caused decades of worth coast deterioration in just a few weeks2. NPPF contains all the important elements of PPS25 (previous policy on flood risk). Measures are being taken to avoid development in the flood plain. The debate on building on flood plains remains a controversial issue. Building on flood plain has resulted in changing the course of rivers which has resulted in the increased flood risk in other areas (The Western Morning News, 31 July 2007; Llanelli Star, 5 December 2012; The Mid-Devon Gazette, 04 December 2012).

Regeneration Project in Lewes District

One of the most significant sites in Lewes District that is currently being progressed for redevelopment proposals is North Street in Lewes. The site lies on the flood plain and is a massive regeneration project. To ensure the safety of new development, a series of options on flood defence are being worked on. Defence strategies are being developed by DEFRA3 and the Environment Agency4. The builders have claimed that they are using the latest design techniques to improve sustainable water management, sustainable urban drainage (SuDs), biodiversity roofs, and various other simple technologies, outlined in the report “A Meaningful Approach”5.

Flood risk management and planning in Netherlands (aka Holland)

Netherlands has a low coastline and is 350km long along the North Sea of which 290km consists of dunes and 60 km is protected by dikes and dams. 30% of the Netherlands lies below sea level which makes the beaches highly vulnerable to erosion and flooding (Louisse and Verhagen, 1990; Talbot, 2007). Every five years, by law, inspection of dikes takes place (telegraph.co.uk, 26 April, 2014). The Dutch have taken a number of measures6 in the past to protect the Netherlands from getting flooded and continue to remain relentless in coast protection. Netherlands has built the world’s largest storm barrier 5.6 miles long called Oosterscheldekering7 and the beach at Kijkduin which is one of the most futuristic flood defence structures in the world. The recent Dutch inventions have been ground-breaking. The sand engine8 and floating houses are noteworthy (telegraph.co.uk, 26 April, 2014). This involved establishment of an agency called “Room for the River” in 2006 (Warner and Van Buuren, 2011). The agency took measures to initiate the transition from “fighting against water” to “living with water”. The measures included lowering dikes, deepening floodplains, widening rivers and moving 200 families to drier areas. They allocated areas of agricultural land that could be allowed for flooding (telegraph.co.uk, 26 April 2014). Floating houses have been built in Maastricht, Amsterdam and Iburg. Some of them float on water and rise with the flood whilst others are built on stilts (NewsRx, 18 September 2011; telegraph.co.uk, 26 April 2014). The architects in the Netherlands are looking at building a raft of floating offices in Rotterdam (telegraph.co.uk, 26 April 2014).

Another interesting example is “The Benthemplein water square at Rotterdam”. Rotterdam is a city located in Dutch Delta and is highly urbanized and has no ‘natural’ relief system for peaks in waterfall. It is the first full-scale water square in the world, an outstanding example of Dutch flood risk management. It is located just outside the city centre. It offers unique facilities for basketball and skating when dry and in the event of heavy rains, the square’s basins (1.7 million litres capacity) retain water from the square keeping it away from sewage system and preventing urban floods (stormwater.wef.org, 3 March 2014; RCI, 2014).

British learning lessons from Dutch

British are now working on their own version of Room for the River. David Rooke, the Environment Agency’s executive director of flood and coastal risk management said “There are a number of trials going on at the moment, in Derbyshire9, North Yorkshire and Devon.” One of the projects by Barker’s firm involved planning undeveloped riverside land in East Norwich. The planned urban area comprises of restaurants and 670 homes complete with floodable parks and play areas. There were green strips between the buildings and streets where the floodwater was allowed to flow without affecting homes. They are creating more space for water. Hence, this provides protection against flooding of the neighbouring areas. Barker is also constructing a floating house on an island in Thames10. Also, Britain is working on materialising the plans for a mini Sand Engine near Bournemouth (telegraph.co.uk, 26 April 2014).

“Adapting to climate change is the most pertinent thing we need to do (telegraph.co.uk, 26 April 2014)”. The storms that hit the UK in autumn 2013 and January 2014 with South east coast badly affected have raised several questions regarding the current standards of coastal defences in England. However, Dutch have been very apt at responding to the challenges faced by the Netherlands. ‘God made the world and Dutch made the Netherlands’ goes the saying (Crawford, Dawsonera, Mehmood and Davoudi, 2009). Britain is learning from the mind-set of the Dutch masters however, it has been argued that Dutch innovations cannot simply be copy pasted since the nature of problems for both countries is different and I totally agree with it.

The major difference between the standards of coast protection schemes is that England designs for 1 in 100 year event whereas the Netherlands designs their coasts for 1 in 10,000 year event. The UK planning system needs to reconsider the probability of severe floods taking place. Dutch believe that 1 in 10,000 is just a number and that it can happen tomorrow (bbc.co.uk, 27 November 2012).

11% of all new buildings have been allowed in the floodplain between 2000 and 2005. PPS25 (previous flood risk policy) allowed building in flood hazard areas if nowhere else was available (TCPA, December 2011). Owing to the geography of Britain, fighting the water has been on the agenda whereas Dutch transitioned from ‘fighting the water’ to ‘living with water’ which involved dramatic changes to planning policies. Where Britain is afraid of building on flood plains, Netherlands is building on water “Floating Houses” and the land is being reclaimed in Rotterdam to build more houses on them.

Conclusion

I am in total agreement with Trudi Elliot, the chief executive of RTPI who recognises a lot of would-be potential development that has not happened yet and is of the view that modern design should effectively mitigate the effects on buildings in the flood prone areas. She also believes that calling for a “planning revolution” and just blaming new development in the flood plain are wide of the mark (The Planner, April 2014). However, I think the severe flood damage is a wakeup call for a “planning revolution” contrary to what Ms. Elliot thinks. Trudi Elliot identifies the need for national debate on the amount of efforts, resources and brainpower we are going to apply to this task (The Planner, April 2014) and I am in total agreement with her thoughts, if our aim is to save 5 million homes that are already at risk of flooding; more than 200 homes that are at risk of complete loss of coastal erosion in the next 20 years. In addition to this, 2,000 homes could become at risk over this period (gov.uk, 2014).

Notes

- Flood events occurred in England and Wales since 1994.

Midlands 1998, England and Wales widespread (2000 and 2001), Boscastle, 2004, Conwy Valley (2004 and 2005), Carlisle (2005), widespread again (2007 and 2008), Morpeth (2008), Birmingham (2009) and Cockermouth (2009). (Town and Country Planning, December 2011)

- “Defra has overall national responsibility for policy on flood and coastal erosion risk management, and provides funding for flood risk management authorities through grants to the Environment Agency and local authorities”.

- The Environment Agency is responsible for taking a strategic overview of the management of all sources of flooding and coastal erosion.

- A Meaningful Approach, 2014. [online] http://northstreetqtr.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/NSQ_Board_13.pdf. [accessed 31 May 2014]

- The storms that hit UK during Autumn 2013 and January 2014 has caused cliffs to crumble, beaches and sand dunes eroded, defences breached, and shorelines and harbours damaged by up to 80mph gales and tidal surges (new.sky.com, 21 February 2014; ). It was reported that “England’s east coast experienced the worst tidal surge in 60 years” (bbc.co.uk, 17 February 2014). The Birling Gap at East Sussex coast is eroding rapidly marking the start of deterioration of white chalk cliffs of the Seven Sisters (new.sky.com, 21 February, 2014) and BBC reported that there has been a large cliff fall at West Bay beach in Portland (theguardian.com, 15 February 2014).

- The Dutch government passed a law in 1990 (Louisse and Verhagen, 1990) which recommended on maintaining the coastline at the current levels. The land is low, flat and vulnerable. Dikes, ditches and narrow canals pass through fields and beneath motorways and, when you reach the urban spaces, they are still there, channels of water running between the streets and tall buildings, dark, tamed and still. The Dutch have tried spits, sea walls, dredging sand from the middle of the ocean and dumping it on the beach to make good, or “nourish”, the damage. Amsterdam, Rotterdam and The Hague have two thirds of their population living on flood-prone land. They have a fantastic network of dikes. If they were laid out, end to end, they would stretch for nearly 50,000 miles (telegraph.co.uk, 26th April, 2014).

- The world’s largest storm barrier 5.6 miles long called Oosterscheldekering was built after the storms of 1953 which left 1800 people dead. It was included in the great plan called ‘Delta Works’ which comprised of a network of sluices, locks, dikes, dams and levees that are vast and complex. It has been named as one of the ‘Seven Wonders of the Modern World’ by the American Society of Civil Engineers. The floods in 1995 forced Dutch to look for another way of protecting their country from flooding. They decided to work with water instead of controlling or fighting it (telegraph.co.uk, 26th April, 2014).

- The Dutch coast loses one million cubic metres of sand per year. 17m euro were spent on getting a 1.25 mile long sand engine in place. It is an arch shaped structure with a lagoon and a lake put and has been designed by the engineers named Stive and de Vriend to pose the greatest possible challenge to the relentless surf. It also adds recreational and ecological value to the place. The sand engine initiative has thus been loved by Nature organisations (telegraph.co.uk, 26th April, 2014).

- One of the trials on Derbyshire’s moorland involves blocking up the ‘grips’ that were dug during 1960s to encourage water run-off. “The grips allowed the water to flow more rapidly into lowland areas. Blocking them will allow the water to be stored on the moors when it rains and then released at a more natural rate.”

- “Meanwhile, a few miles from the village in which I live, Barker’s been busy building a floating house. “This is where we really did learn from the Dutch and their amphibious houses,” he says, of the construction in Marlow. “The house is on an island in the Thames. Predictions are that the flood plain is going to be higher than where the building currently sits. We couldn’t lift it up because it was in a conservation area, so we excavated the ground and had the house float on the water.” (telegraph.co.uk, 26 April, 2014)

References

‘100% climate proof : Projecten : Benthemplein: the first full-scale water square :: Rotterdam Climate Initiative’, (2014) [online], available: http://www.rotterdamclimateinitiative.nl/en/100procent-climate-proof/projecten/benthemplein-the-first-full-scale-water-square?portfolio_id=194 [accessed 31 May 2014]

Anonymous2007, Jul 31. Building on flood plains is brainless. The Western Morning News, 11.

Anonymous2012, Dec 05. Building on flood plain. Llanelli Star, 10.

Anonymous2012, Dec 04. ‘No building on flood plains’. The Mid-Devon Gazette, 18.

‘BBC News – 10 key moments of the UK winter storms’, (2014) [online], available: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-26170904 [accessed 29 May 2014]

“Climate Change; Floating houses”, 2011, NewsRx Health & Science, , pp. 117.

‘David Cameron’s statement on the UK storms and flooding – Speeches’, (2014) [online], available: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/david-camerons-statement-on-the-uk-storms-and-flooding [accessed 30 May 2014]

Dawsonera., Mehmood, A., Davoudi, S. and Crawford, J. (2009) Planning for climate change: strategies for mitigation and adaptation for spatial planners, London: Earthscan.

‘Eleven dead as huge storm batters UK, France and Netherlands; gusts of up to 160km/h’, (2014) [online], available: http://www.news.com.au/world/killer-storm-jude-smashes-britain-and-europe/story-fndir2ev-1226747921666 [accessed 30 May 2014]

‘Eurovision Case study Holland Coast’, [online], available: http://copranet.projects.eucc-d.de/files/000139_EUROSION_Holland_coast.pdf [accessed 30 May 2014]

‘First Full-Scale Water Square Opens in Rotterdam’, (2014) [online], available: http://stormwater.wef.org/2014/03/first-full-scale-water-square-opens-rotterdam/ [accessed 30 May 2014]

‘Flooding And Erosion Damage Across The UK’, (2014) [online], available: http://news.sky.com/story/1215005 [accessed 30 May 2014]

I., I. P. o. C. C. W. G. and Parry, M. (2007) Climate change 2007: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

‘Investing for the future’, (2009) [online], available: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/292923/geho0609bqdf-e-e.pdf [accessed 30 May 2014]

Mary, Z., Amalia, F.-B., David, S. and James, K. J. a. A. (2011) ‘Impacts of climate change on disadvantaged UK coastal communities’, [online], available: http://www.jrf.org.uk/sites/files/jrf/disadvantage-communities-climate-change-full.pdf [accessed 30 May 2014]

Merrilee, B. (2000) ‘Climate Change Policies in the Netherlands: Analysis and Selection’, in Workshop on Best Practices in Policies and Measures, Copenhagen,

Michael, H. (27 November 2009) ‘Rising sea levels: A tale of two cities’, [online], available: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/8362147.stm [accessed 30 May 2014]

- van Koningsveld and J. P M. Mulder (2004) Sustainable Coastal Policy Developments in The Netherlands. A Systematic Approach Revealed. Journal of Coastal Research: Volume 20, Issue 2: pp. 375 – 385.

- Pitt: Lessons from 2007 Floods. An Independent Review. Pitt Review Report. The Stationary Office, 2009 [online] http://www.cabinetoffice.gov.uk/the pittreview/final_report.aspx [accessed on 30 May 2014]

National Population Projections 2008 – Based. Office for National Statistics, 2010

‘North Street Quarter’, (2013) [online], available: http://northstreetqtr.co.uk/ [accessed 30 May 2014]

Programme., U. N. E. (1993) The impact of climate change, Nairobi: United Nations Environment Programme.

- Pall et al.: Anthropogenic greenhouse gas contribution to England and Wales in autumn 2000’. Nature, 2011, Vol, 470, 382-5

Rebecca, P. (2009) ‘Aquatecture: Water-based Arch itecture in the Netherlands’.

‘Reducing the threats of flooding and coastal change – Policy’, (2014) [online], available: https://www.gov.uk/government/policies/reducing-the-threats-of-flooding-and-coastal-change [accessed 30 May 2014]

Schouten, J. J. (2005-06) ‘Technical feasibility of a large-scale land reclamation’, [online], available: http://repository.tudelft.nl/view/ir/uuid:93632b30-0ae0-474f-8eb5-1f1496d23884/ [accessed 30 May 2014]

Scoones, S. (2003) Climate change: our impact on the planet, London: Hodder Wayland.

Urquhart, C. (2014) ‘UK storms and flooding’.

TALBOT, D., 2007. Saving Holland. Technology review, 110(4), pp. 50-56.

The Journal of Town and Country Planning Association. December 2011. Vol. 80 No. 12

The Planner, April 2014. Royal Institute of Town Planners.

Warner, J. and Buuren, A. v. (2011) ‘Implementing Room for the River: narratives of success and failure in Kampen, the Netherlands’.

Will, S. (26 April 2014) ‘Flooded Britain: how can Holland help?’, [online], available: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/art/architecture/10769974/Flooded-Britain-how-can-Holland-help.html [accessed 26 May 2014].

- Finlinson, D. Crichton, S. Evans, J. Salt and S. Waller and the Loss Prevention Council: Inland Flooding Risk – Issues Facing the Insurance Industry. General Insurance Research Report 10. Association of British Insurers, 2000